The Unsolved Case of the Cleveland Torso Murderer

- miawsk2022

- Feb 17, 2022

- 12 min read

Updated: Jan 27, 2024

The Cleveland Torso Murderer, also known as the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run, was an unidentified serial killer who was active in Cleveland, Ohio, United States, in the 1930s. The killings were characterized by the dismemberment of twelve known victims and the disposal of their remains in the impoverished neighborhood of Kingsbury Run. Most victims came from an area east of Kingsbury Run called "The Roaring Third" or "Hobo Jungle", known for its bars, gambling dens, brothels, and vagrants. Despite an investigation of the murders, which at one time was led by famed lawman Eliot Ness, then Cleveland's Public Safety Director, the murderer was never apprehended.

The official number of murders attributed to the Cleveland Torso Murderer is twelve, although recent research has shown there could have been as many as twenty. The twelve known victims were killed between 1935 and 1938. Some investigators, including lead detective Peter Merylo, believe that there may have been thirteen or more victims in the Cleveland, Youngstown, and Pittsburgh areas between the 1920s and 1950s. Two strong candidates for addition to the initial list of those killed are the unknown victim nicknamed the "Lady of the Lake," found on September 5, 1934, and Robert Robertson, found on July 22, 1950.

During the time of the "official" murders, Eliot Nessheld the position of Public Safety Director of Cleveland, a position with authority over the police department and ancillary services, including the fire department. While Ness had little to do with the investigation, his posthumous reputation as leader of The Untouchables has made him an irresistible character in modern "torso murder" lore. Ness did contribute to the arrest and interrogation of one of the prime suspects, Dr. Francis E. Sweeney. In addition, he personally conducted raids into hobo shanties and eventually burned down Kingsbury Run, from which the killer took his or her victims, in an attempt to stop the murders. At one point in time, the killer taunted Ness by placing the remains of two victims in full view of his office in city hall.

Between 1935 and 1938, a serial killer murdered and dismembered at least 12 victims - only 2 of which were ever positively identified. This killer is officially unidentified, yet researchers of today are quite certain who committed these horrible crimes.

During the 1920s, Cleveland was a city on the rise. The population was booming, with new immigrants from around the globe joining the workforce that served the backbone of the city's industrial and manufacturing economy. The city's wealthy lived in the grand homes along Millionaire's Row and supported many new educational and cultural institutions.

However, Cleveland was hit hard by the Great Depression of 1929. During the 1930s, city leaders worked to help its struggling citizens and raise the community's morale. The Great Lakes Exposition and the Republican National Convention were scheduled for 1936.

Against this backdrop of a large city improving economically, one of the most prolific and gruesome serial killers of all time carried out his acts of horror, distracting the citizens of our city from the pride and prosperity of the times. Thirteen people were brutally murdered over the course of four years, beginning in 1934. All of them decapitated, most of them while they were still alive. Then, the murders ended as abruptly as they began. Although Safety Director Eliot Ness claimed to have solved the crimes, no suspect was officially identified, and no one was brought to trial. To this day the Kingsbury Run Murders remain one of the most sensational and intriguing unsolved crimes in our nation's history.

Kingsbury Run is a prehistoric riverbed running from The Flats (the area along the Cuyahoga River near Lake Erie) to about East 90th Street. Train and rapid transit tracks still run through the Run. Bordered on the north by Woodland Avenue and on the south by Broadway Avenue, Kingsbury Run was a dark, dreary and dangerous place in the 1930s. The dispossessed of the Great Depression lived in appalling conditions. Trash and filth dominating the makeshift “hobo jungle” that occupied much of the Run. These people, most of them transients, often rode the rails to escape the brutal Cleveland winters or simply to keep moving. The area just to the east of the Run was known as “The Roaring Third” Police Precinct home to bars, brothels, flophouses and gambling dens. In this grim setting, the most notorious murder case in Cleveland’s history would unfolded.

September 1934: A young man found the remains of a woman in her mid-30s. The torso with thighs still attached, but amputated at the knees, had washed up on the shores of Lake Erie just east of Bratenahl. Cuyahoga County Coroner A.J. Pearse noted that a chemical preservative on the skin which had turned it red, tough and leathery. The subsequent search yielded just a few other body parts, but her head was never found. The woman was never identified as soon referred to as “The Lady of the Lake”. It wasn’t until two years later that this find was included in the official killing total and thus became known as victim #0. It would be another year before the case began officially, and then it would be in another part of the city-the now infamous Kingsbury Run.

September 1935: Two teenage boys discovered the decapitated, emasculated corpse of a white male at the base of Jackass Hill, where East 49th Street dead ends into Kingsbury Run. The body, naked save for a pair of socks, was clean and drained of blood, with rope burns around both wrists. Coroner Pearse determined the cause of death had been decapitation. Fingerprints identified this victim as Edward Andrassy, a twenty-eight-year old white male who frequented the Roaring Third. While searching the crime scene, police discovered a second body nearby, also decapitated and emasculated. It appeared to be covered with the same chemical preservative as the Lady of the Lake. This body apparently had been dead for at least a couple of weeks. The forty-year old white male was never identified.

January 1936: A woman discovered parts of a woman's body neatly wrapped in newspaper and packed in two half-bushel baskets. The baskets were left alongside the Hart Manufacturing building on Central Avenue near East 20th Street. The rest of the remains, except the head were recovered about ten days later in a nearby vacant lot on Orange Avenue. As with Victims #1 and #2, the cause of death had been decapitation. In this case, however, the killer waited for rigor mortis to set in before disarticulating the rest of the body. Cleveland Police used fingerprints to identify Victim #3 as Florence Polillo, a waitress and bar maid, who at the time of her death resided at East 32nd Street and Carnegie, right on the edge of the Roaring Third.

A plaster cast of the man’s face and a diagram showing all the tattoos on his body were displayed at the Great Lakes Exposition. More than 11 million people attended the exposition in the two summers it was open, but none could identify “the tattooed man,” one of at least a dozen “torso murders” that plagued northern Ohio—and possibly beyond.

September 1934: A young man found the remains of a woman in her mid-30s. The torso with thighs still attached, but amputated at the knees, had washed up on the shores of Lake Erie just east of Bratenahl. Cuyahoga County Coroner A.J. Pearse noted that a chemical preservative on the skin which had turned it red, tough and leathery. The subsequent search yielded just a few other body parts, but her head was never found. The woman was never identified as soon referred to as “The Lady of the Lake”. It wasn’t until two years later that this find was included in the official killing total and thus became known as victim #0. It would be another year before the case began officially, and then it would be in another part of the city-the now infamous Kingsbury Run.

The victim's lower torso, thighs still attached but the knees amputated, were discovered by a young man washing up on the shores of Lake Erie just east of Bratenahl. A subsequent search only recovered a few body parts. The head was not recovered. The medical coroner of Cuyahoga County, A.J. Pierce, noted that there was a chemical preservative on the skin that made it red, leathery, and tough.

The victim, called "Lady of the Lake," is also referred to as "Victim #0" or "Victim #1" of the Cleveland Torso Killer. Between 1935-1938, the Cleveland Torso Killer was responsible for the murder and dismemberment of twelve transients and hobos in which only two were ever identified.

The rest of the remains, except the head were recovered about ten days later in a nearby vacant lot on Orange Avenue. As with Victims #1 and #2, the cause of death had been decapitation. In this case, however, the killer waited for rigor mortis to set in before disarticulating the rest of the body.

The police department put detectives Peter Merylo and Martin Zelewski on the case full time. They moved deftly through the seedy underworld that constituted the Run and the Roaring Third, often dressing the part while off-duty. By the time the case had run its course, the two had interviewed more than fifteen hundred people, the department as a whole more than five thousand. This would be the biggest police investigation in Cleveland history.

A letter sent to Cleveland's police chief in December 1938, a few months after the last victim is found.

The unsolved nature of killings, added to the fact that the man trying to solve them was the most famous crime solver in America, also adds to the fascination. As does the fact that it’s one of the earliest known serial killer cases in America.

“People like the puzzle of it, looking for connections, you want to solve it,” says Pulley. “If the killer had been found, like Charles Manson, it would be different.”

“Because crime is so forbidden, it’s revolting and fascinating at the same time,” says the author, who has just completed her fourth book, a ghost story set in a Shaker Heights house.

“Most of us, myself included, when you look at these heinous crimes and darkest sides of humanity, you want to look at them to try to understand the nature of evil.

Several noncanonical victims are commonly discussed in connection with the Torso Murderer. The first was nicknamed the "Lady of the Lake" and was found near Euclid Beach on the Lake Erie shore on September 5, 1934. Only parts of her were found and matched with parts found at another shore in Perry. She had an abdominal scar from a likely hysterectomy which was common and made it more difficult to identify her. After she was found, several people reported seeing body parts in the water, including a group of fisherman who believed to have seen a head. She was found virtually in the same spot as canonical victim number 7. Some researchers of the Torso Murderer's victims count the "Lady of the Lake" as victim number 1, or "Victim Zero". Like the Lady of the Lake, John Doe I had some kind of substance on his skin (though his skin abnormalities could possibly be due to burning) when his body was found; however, at the time the similarities were not connected. The chemical was believed to have been a substance using lime chloride. It is supposed that the killer meant to use a quickening lime to decompose the bodies quicker but mistakenly used lime that would preserve bodies instead.

The headless body of an unidentified male was found in a boxcar in New Castle, Pennsylvania, on July 1, 1936. Three headless victims were found in boxcars near McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, on May 3, 1940. All bore similar injuries to those inflicted by the Cleveland killer. Dismembered bodies were also found in the swamps near New Castle between the years 1921 and 1934 and between 1939 and 1942. In September 1940 an article in the New Castle News refers to the killer as "The Murder Swamp Killer". The almost identical similarities between the victims in New Castle to those in Cleveland, Ohio, coupled with the similarities between New Castle's Murder Swamp and Cleveland's Kingsbury Run, both of which were directly connected by a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line, were enough to convince Cleveland Detective Peter Merylo that the New Castle murders were the work of the "Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run". Merylo was convinced the connection was the railroad that ran twice a day between the two cities; he often rode the rails undercover looking for clues to the killer's identity.

On July 22, 1950, the body of 41-year-old Robert Robertson was found at a business at 2138 Davenport Avenue in Cleveland. Police believed he had been dead six to eight weeks and appeared to have been intentionally decapitated. His death appeared to fit the profile of other victims: He was estranged from his family, had an arrest record and a drinking problem, and was on the fringes of society. Despite widespread newspaper coverage linking the murder to the crimes in the 1930s, detectives investigating Robertson's death treated it as an isolated crime.

In 1939 the "Torso Killer" claimed to have killed a victim in Los Angeles, California. An investigation uncovered animal bones. In addition to the murders in Cleveland it is also suspected that there are connected murders before and after in Sandusky and Youngstown, as well as New Castle, PA, and Selkirk, NY. If they are connected this would raise the body count, and raise more questions about travel ability. It would also create a longer timeline of murders and victims over the span of the years. In a time where most major travel was still by railway, and Cleveland being a major hub between some of these cities, it would be much more difficult to find viable suspects.

While the case is officially unsolved, many believe the identity of the Torso Murderer of Kingsbury Run has been known since the 1930s. Mysterious Dr. X was investigated by the police and interrogated by Eliot Ness, but no physical evidence was found linking him to the crimes.

Most likely, Dr. X was Francis E. Sweeney, an intelligent, skilled and very troubled surgeon who lived near Kingsbury Run. Dr. Sweeney had the surgical know-how as well as access to facilities ideally suited for dismembering bodies. Despite a week-long interrogation by Eliot Ness and other high-level investigators, Sweeney never confessed. However, immediately after Sweeney committed himself to a sanitorium, the murders stopped.

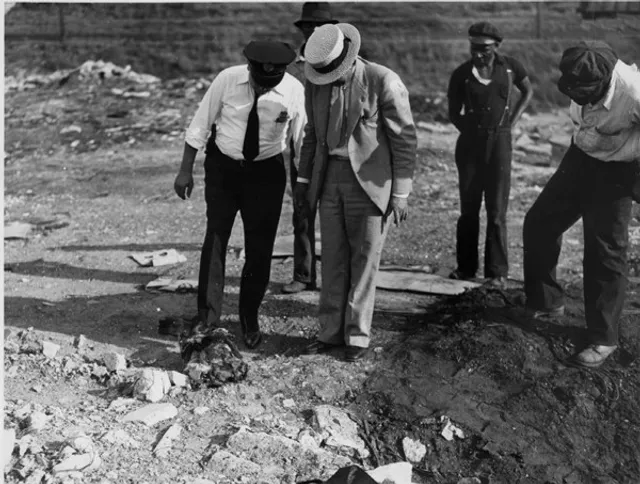

Cuyahohoga County Coroner Samuel Gerber, M.D. Coroner Samuel R. Gerber, right, of Cleveland, and two of his assistants examine the skull, pelvic bones and spinal column of the 11th and 12th victims of the "torso killer," Aug. 18, 1938. Neither of the last two victims has been identified.

Cuyahoga County Coroner Samuel Gerber examines a woman's foot.

Both Coroner Pearse and Coroner Gerber enlisted the help of outside experts to help identify both the victims and the killer. Pearse gathered together Safety Director Eliot Ness, Police Chief Matowitz, SIU head Cowles, County Prosecutor Frank Cullitan, Head of Homicide Hogan, police detectives, several psychiatrists, doctors, and pathologists at a “Torso Clinic” where they analyzed and discussed the evidence collected to date. Gerber hosted the annual conference of the National Association of Coroners in late August 1937, also with a goal to use this collected wisdom to help identify the victims and the murderer. Gerber also created and shared a “Survey of Anatomical Findings and Related Facts of the So-Called Torso Murder Victims.”

Most investigators consider the last canonical murder to have been in 1938. One suspected individual was Dr. Francis E. Sweeney. Sweeney worked during World War I in a medical unit that conducted amputations in the field. Sweeney was later personally interviewed by Eliot Ness, who oversaw the official investigation into the killings in his capacity as Cleveland's Safety Director. During this interrogation, Sweeney is said to have "failed to pass" two very early polygraph machine tests. Both tests were administered by polygraph expert Leonard Keeler, who told Ness he had his man. Nevertheless, Ness apparently felt there was little chance of obtaining a successful prosecution of the doctor, especially as he was the first cousin of one of Ness's political opponents, Congressman Martin L. Sweeney, who had hounded Ness publicly about his failure to catch the killer.

The killings apparently stopped after Sweeney voluntarily entered institutionalized care shortly after the last official murders were discovered in 1938. From his hospital confinement, Sweeney would mock and harass Ness and his family with threatening postcards into the 1950s. He died in a veterans' hospital at Dayton in 1964.

Ness was tormented by postcards from a possible suspect from an asylum. During the time of the "official" murders, Eliot Ness held the position of Public Safety Director of Cleveland, a position with authority over the police department and ancillary services, including the fire department.

July 1939: County Sheriff Martin O’Donnell arrested fifty-two-year-old Bohemian brick layer Frank Dolezal for the murder of Flo Polillo. Dolezal had lived with her for a while, and subsequent investigation revealed he had been acquainted with Edward Andrassy and Rose Wallace.

His “confession” turned out to be a bewildering blend of incoherent ramblings and neat, precise details, almost as if he had been coached. Before he could go to trial, Dolezal was found dead in his cell. The five foot eight Dolezal had hanged himself from a hook only five feet seven inches off the floor. Gerber’s autopsy revealed six broken ribs, all of which had been obtained while in the Sheriff’s custody. To this day, few believe Frank Dolezal was the torso killer.

The Kingsbury Run Murders remain one of the most perplexing cases in our nation’s criminal history. Rumors abound as to who may have been the killer. One thing is very clear: Eliot Ness had a suspect who he believed was undoubtedly the killer. This suspect continued to taunt Ness for years after the killings had stopped. All official police records on this case have been lost, destroyed, or removed.

This is a close up of one of the three mutilated bodies found in box cars assigned to a scrap heap near Pittsburgh, Penn., May 3, 1940. Note the word "Nazi" carved into the chest. Authorities advanced the theory that the three were victims of the "mad butcher of Kingsbury run," blamed for 12 "torso murders" in Cleveland, Ohio.

Investigators look at the dismembered head of one of the victims.

Knives carried by torso murder suspect Mike Pesanka.

In 1947—the same year Ness unsuccessfully ran for mayor of Cleveland—a woman, later identified as Elizabeth Short, was found murdered in Leimert Park in Los Angeles.

Short was cut in half, her intestines were removed, and she was drained of her blood—all similar hallmarks to the Torso Murders. She became known as the Black Dahlia, and her murder has one more thing in common with the Torso Murders: It remains unsolved.

After the authorities ran out of suspects, and no more bodies were found, the case ran cold.

Since 1939, no new information has been found on the Cleveland Torso Murderer.

Ness died at 54 in 1957, broke and broken; the man who was once the nation’s top Prohibition agent now had a serious drinking problem of his own. Six months after his death, his memoir, The Untouchables, was published and became the basis for a television show a year later. Ness has remained a pop culture icon ever since. Forty years after his death, Ness was given a funeral with full police honors in Cleveland, and his ashes were scattered at Lake View Cemetery on the city’s east side—not far from Kingsbury Run, where the Mad Butcher left a trail of body parts.

SEE ALSO...

Comments